Destinations Around The World To See The Strangest Natural Phenomena

We live in a society surrounded by artificial inventions like motor transport, artificial intelligence, and the internet, but nothing is more impressive than Mother Nature. Just look at natural happenings like volcanoes, where hot lava from deep inside the earth flows onto the ground, or earthquakes, where tectonic forces move to create jolting blows. Even the fact that our planet continues to revolve around a bright star millions of miles away in outer space is incredible.

However, you don't need to be a scientist to appreciate the wonder of incredible phenomena all over our planet, like a glacier that spouts blood-colored liquid, a cloudy river flowing underwater, and a massive boulder perched on a hill that is determined not to move. Instead, all you need is nature because these wild sights serve to show how miraculous our planet really is. We have rounded up the strangest natural phenomena from all over the world that have our heads rolling.

Lake Natron in Tanzania

If you're wondering why Lake Natron in Tanzania, Africa, has been called the Deadly Red Lake, look at its name. Natron is sodium carbonate, and the lake has so much sodium carbonate — otherwise known as soda ash — that it has a pH level that can rise above 10, making it deadly to both humans and most animals. Like ammonia, which has a similar pH level, the lake can damage skin and eyes and even embalm beings that end up in its waters. Ancient Egyptians used sodium bicarbonate to mummify their loved ones, and when animals pass away in the lake, the sodium bicarbonate does the same to their bodies.

So how did this lake on the border of Kenya, which luckily has no outlets, become so highly alkaline? Look to its volcanic neighbor, Ol Doinyo Lengai. The material of the active volcano has combined with the lake's waters, creating a liquid so full of salt, soda, magnesite deposits, and cyanobacteria that most animals that drink from it die. However, one animal seems immune to its poison — flamingoes. The hot lake, which can reach 140 degrees Fahrenheit, attracts over a million flamingoes at some times, and they love gorging on the lake's cyanobacteria-rich algae, which helps keep them pink but doesn't affect their health. Lake Natron, which measures 35 by 15 miles, is the biggest breeding area on the planet for the lesser flamingo species.

Caño Cristales in Macarena National Park, Colombia

It looks more like a Bob Ross painting than a river, but Caño Cristales in Macarena National Park, Colombia, is as real — and colorful — as it gets. Known as the "River of Five Colors," Caño Cristales showcases red, yellow, green, blue, and black hues best seen between July and October, and the tens of thousands of tourists that have flocked here over the years have aquatic plants called Macarenia clavigera to thank for that. Summer and fall are when the river has the perfect mix of sunshine and water level to allow the plants, which cling to the Caño Cristales' quartzite rock, to strut their stuff, and this is the only spot in the world where it happens.

However, Caño Cristales has arguably been too popular. The 15,000 tourists who once visited the 62-mile river every year worried scientists that the river could become damaged, so today, only a maximum of 200 people can visit per day. They have to be committed to seeing the river, too. To reach it, tourists must fly to Villavicencio, then to La Macarena, and then find a guide who can take them to the remote mountain range leading to the river. You can even swim in the river, but do not wear sunscreen, bug spray, or other skin products that could damage its colorful inhabitants.

The Bermuda Triangle in the Atlantic Ocean

The world is full of mysterious spots, but few cover 500,000 square miles. However, that's precisely the area of the Bermuda Triangle, which stretches from Florida to Bermuda to the Greater Antilles islands. It's here in the Atlantic Ocean that more than 50 ships and 20 planes have simply disappeared at least from the mid-19th century, all without a trace of wreckage or distress calls left in their wakes. However, even though explanations of "The Devil's Triangle" have been tied to everything from aliens to the mythical city of Atlantis, the real reason is likely a lot less supernatural.

The Bermuda Triangle sits in an area home to various deadly environmental phenomena, including unexpected storms and waterspouts, which are essentially sea tornadoes. Large deposits of methane gas are found under the ocean floor in the area, which could cause flammable methane eruptions that can set a boat engine on fire or cause water pressure that could force a ship underwater. Also, many tropical storms travel through the Bermuda Triangle, producing 100-foot waves that could easily swallow a ship. Since the area also has many islands, there are also many unexpected spots with shallow water, which could damage a ship. Moreover, the area of the Bermuda Triangle sees heavy traffic for shipping and flights, so we're more likely to hear about disappearances here than in other places.

The Magnetic Hill in Moncton, Canada

We pity the driver who first discovered (about 100 years ago) that his car seemed to be rolling uphill on a country road in Moncton, New Brunswick (Canada). Today, everyone loves Magnetic Hill, a "mystery spot" tourist attraction that costs $7 Canadian to access per car between May and October. However, it's more of an optical illusion than an area lacking gravity. Even though Magnetic Hill looks like it's heading uphill, it's a downhill run that tilts at a different angle and has no horizon to redirect our brains to the truth. The trees on these gravity hills appear to bend without the sight of the horizon, further obstructing our reality, which can be made even more prominent when there are other hills in sight. Even nearby rivers can appear to be flowing uphill in areas like these.

Magnetic Hill is one of many gravity hills worldwide, but this one is one of the most well-known – and is one of the most popular natural attractions in Canada. All drivers need to do to enjoy its mind-bending qualities is put their cars in neutral and keep their feet off the brake, and the car will seem to slowly roll uphill this 1,600-foot stretch of road.

Moeraki Boulders in Otago, New Zealand

No one is completely sure why around 50 giant boulders are covered in mineral deposit cracks on the beaches of Otago, New Zealand, but their mystique and massiveness — most of them have a diameter of 7 feet – have brought tourists to the area since the 19th century. These days, they're protected by law, as many of the smaller boulders (the biggest ones weigh 7 tons) were taken by tourists prior to the legislation. Some of them are also protected in the nearby Otago Museum because, unfortunately, they're not easily replaced.

Most people believe that the boulders came to be 60 million years ago through a process called concretion. Millions of years later, erosion allowed the then-formed boulders to break free of the surrounding mudstone and eventually end up on the shore. Other theories also exist, like perhaps they're the cracked eggs of aliens who now exist among the general public, or they ended up in Otago after a canoe known as Āraiteuru was destroyed nearby and lost the boulders. The Moeraki Boulders aren't the only ones of their kind, but the ones you'll see in Otago are the biggest and the roundest. If you want to see the boulders for yourself, visit the beaches during low tide.

Racetrack Playa in Death Valley National Park, California

For nearly a century, scientists were left scratching their heads at how hundreds of heavy rocks seemed to have been magically dragged across Racetrack Playa, a dried-up lake in Death Valley National Park, California, in what has been called one of the strangest natural wonders of the world. However, in 2014, they finally cracked the code as to how the rocks — some that weighed up to 700 pounds and traveled up to 1,500 feet – ended up being so mobile. When the flat, 3-by-2-mile lakebed receives a little bit of water, which then freezes during the chilly weather of the wintertime, wind can push the rocks hundreds of feet across the wet, icy ground. This happens incredibly slowly, to the point where visitors could have seen the rocks moving without even knowing it.

To see the fascinating trails of these rocks, you need to want an adventure that's much more thrilling than a rock slowly being pushed by wind and ice. That's because it takes three-and-a-half hours to traverse the 27 miles needed to get to Racetrack Playa from the Furnace Valley Visitor Center on a coarse road that can often only accommodate one car in a given spot and is known to cause flat tires. Plus, the heat is intense here in the summer, there's no cell service, and you should probably only drive a 4x4 high-clearance vehicle.

Richat Structure in Mauritania

If you've ever seen a space movie, you've probably seen the Richat Structure – the so-called "Eye of the Sahara" in the Sahara Desert of Mauritania. At 25 miles in diameter, it is so large that it wasn't discovered until people began rocketing into outer space and could finally see it in all its glory. Appearing like a bullseye due to its rock ridges and valleys of varying heights, it's more than something cool to see from space — it's a historical and geographic wonder that people once believed was formed by a crater. Since stone tools and hand axes have been found here, it's even been thought that early humans lived at the Richat Structure.

Today, it's thought that the Richat Structure began to form around 100 million years ago when the tectonic plates of South America began to move away from what is now Africa. When that happened, the lithosphere weakened, enabling the underground magma to rise and disturb the earth through erosion, creating a dome-like shape. As millions of years went by, water and wind in the then not-so-dry desert created the circle-like Richat Structure, made up of materials like sandstone, carbonatite, black basalt, rhyolite, and more. Like a tree trunk, the ridges of the Richat Structure showcase its age, as its outer layers are its newest formations.

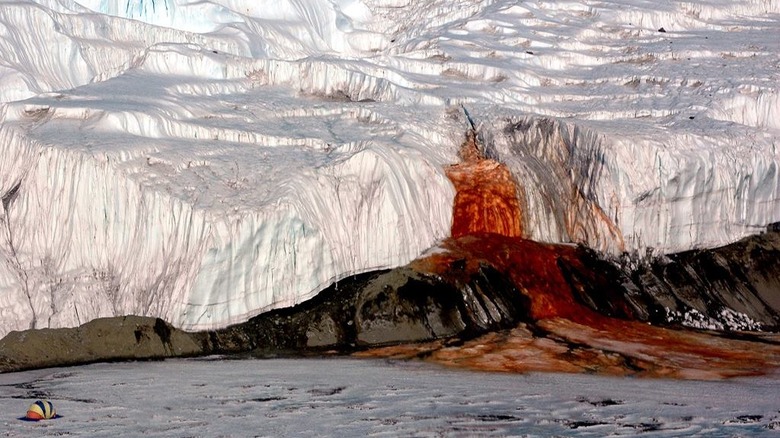

Blood Falls in Taylor Valley, Antarctica

Why is a freezing 19-degree Fahrenheit red waterfall oozing from five stories high on a glacier in Taylor Valley, Antarctica? That question has stumped scientists since 1911, when Australian geologist Thomas Griffith Taylor discovered the strange and creepy phenomena in the valley that's now named after him during one of the first-ever explorations of the region. Although the red coloring of the briny water was initially thought to be due to red algae or possibly iron oxide, it's now known that a rarely iron-rich lake deep underneath the glacier is to blame since iron causes a red coloring after oxidation (just like how iron turns reddish when it rusts). It also stops water from freezing, as saltwater needs colder temperatures to freeze than water. Still, scientists aren't sure what pushes the brine outside the glacier's underbelly in the first place, but it makes for one of the most beautiful landscapes in the world.

Plus, since saltwater melts ice — which is also why we salt our driveways after snow — Blood Falls can flow due to the salty water running over the glacier's icy exterior. Other elements, like chlorine, magnesium, and sodium, also exist in the makeup of the falls, causing the red color. It seems all the stranger since it takes place only at the coldest glacier on the planet with flowing water.

Eternal Flame Falls in Orchard Park, New York

Since at least the 17th century, an 8-inch flame has danced inside a grotto within the 35-foot Chestnut Ridge Falls in Shale Creek Preserve, New York. Otherwise known as Eternal Flame Falls, the flame was likely lit by indigenous people, making for one of the few hundred eternal flames to exist on the planet. As to how that flame stays lit inside the falls' grotto, no one is entirely sure, and it has even been called one of the most mysterious places on the planet. Initially, it was thought that the flame stayed lit due to natural gas being created from pockets inside the shale bedrock of the falls. That was found to be untrue since the shale bedrock isn't hot enough to produce natural gas.

However, something keeps that natural gas going, which passersby continue to light whenever the flame goes out due to wind or other factors. To see it for yourself, follow the half-mile Eternal Flame Trail in the park, and bring a lighter in case you are one of the lucky few needed to re-ignite this wonder. You'll know you're in the right place when you notice the rotten egg scent of the natural gas. To get the full effect of the magnificent waterfall and flickering flame, visit during the early spring, when wet conditions strengthen the waterfall.

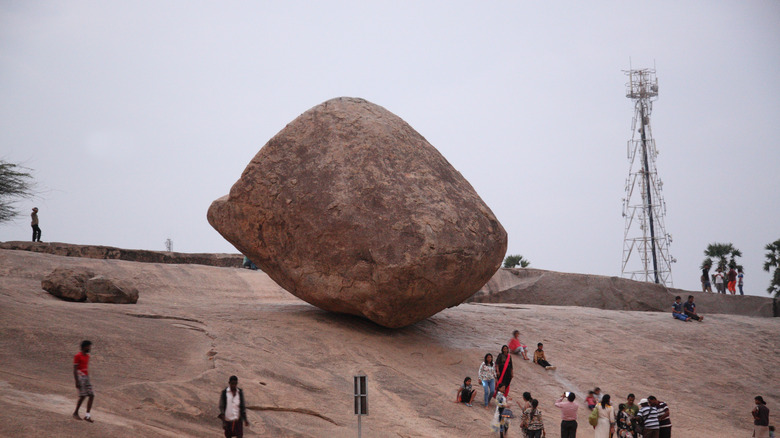

Krishna's Butterball in Mahabalipuram, India

Although Krishna's Butterball — a 250-ton boulder that stands 20 feet high and 16 feet across — may look like it's about to roll down a 45-degree hill in Mahabalipuram, India, you're likely to be fine grabbing some respite from the sweltering heat under it or posing for a Leaning Tower of Pisa-like photo beneath it. Kids can even slide underneath it, and goats often hop atop it. That's because, according to legend, God placed this boulder upon the hill, and neither Pallava King Narasimhavarman(a seventh-century emperor), a team of elephants, several earthquakes, or tsunamis have been able to move the 1200-year-old rock since.

It's not entirely surprising that they couldn't move it, as it's also been said the boulder weighs more than Machu Picchu in Peru. Tourists can thank friction and gravity for this unique attraction, as the boulder likely stays in place in Mahabalipuram, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, due to both factors. And they can also thank Lord Krishna in Hindu mythology for its name. According to legend, when the lord was a baby, he loved his butter and would often snipe it from his mother's butter jar. Thus, the boulder is simply a mound of butter that the lord dropped from the sky– hence the name Krishna's Butterball.

Angelita Cenote in the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico

You don't see this on your average scuba trip. If you dive down about 100 feet into a 200-foot pool in a jungle in Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula, you'll see something truly bizarre — a supposed river flowing underwater. However, it's actually a hydrogen sulfide cloud caused by saltwater and freshwater being forced to meet due to a sinkhole (called a cenote) propelled by a limestone collapse, destroying the rock that once kept the saltwater separate. Unlike many nearby cenotes, this one isn't connected to any underwater caves.

The change in salinity causes the cloudlike river, which is called the Angelita Cenote (Little Angel Cenote). Even though the "river," nestled in an otherwise normal-appearing pool of fresh water, looks serene, it's anything but. The hydrogen sulfide is toxic, as well as murky, and was once believed to be a portal to the underworld. It also contains methane and is a whopping five times saltier than the ocean, although it's safe for humans to dive into since they will be breathing air from their scuba tanks. Like Eternal Flame Falls, you'll know you're close when you smell the rotten eggs underwater.

Cave of the Crystals in Naica, Mexico

It seems incredible that the Cave of the Crystals, full of colossal crystals weighing up to 12 tons and measuring more than 35 feet tall, was discovered only slightly more than two decades ago. However, it is a little clearer once you know how dangerous the cave is. Located in Naica, Mexico, the humidity is always more than 90%, and the temperature is always 136 degrees Fahrenheit, which means those researching the 100-by-30-foot cave need to wear special protective suits.

That's a price only researchers can pay to see the most enormous selenite gypsum crystals on the planet, formed 26 million years ago. The cave is closed to the public. The phenomenon was created when underground magma headed toward the planet's surface. It made the Sierra Naica Mountain and provided the heat needed to dissolve the existing anhydrite deposits in its caverns and enrich them with calcium and sulfate. Meanwhile, the deposits were covered in mineral-rich waters, which allowed the enormous crystals to form for up to a million years as the waters slowly cooled — and the slower they cooled, the bigger the crystals grew. At 136 degrees Fahrenheit, nothing is cooling very quickly.