The Most Dangerous Jellyfish You Can Encounter At The Beach

Of all our planet's weird and wonderful creatures, jellyfish are among the strangest. To our human eyes, they look positively alien — it is little wonder that the realms of science fiction often take inspiration from jellyfish to depict extra-terrestrial visitors, from James Cameron's "The Abyss" to Jordan Peele's "Nope" and beyond.

It's hard to think of many other creatures that are less like us, and jellyfish are truly remarkable. They may look ethereal with bodies made from up to 95% water, but they are actually deadly predators who use their tentacles to ensnare and sting their prey, which ranges from tiny marine plants to fish and crustaceans. They're very old, too: Without brains, hearts, or lungs, jellyfish have floated around in our seas for over 500 million years.

While the majority of planet Earth's 200 known species of jellyfish are mostly harmless, some of the most venomous are very deadly indeed. Around 100 deaths are attributed to jellyfish stings each year (per Technology Networks Genomic Research), which is more than the combined total of fatalities for encounters with sharks, stingrays, and sea snakes. One of the most dangerous species is the box jellyfish, which can pose such a threat to swimmers and beachgoers that they even have their own warning category in the U.S. Weather Report. Here are five types of jellyfish you should definitely try to avoid while vacationing by the sea.

Chironex fleckeri

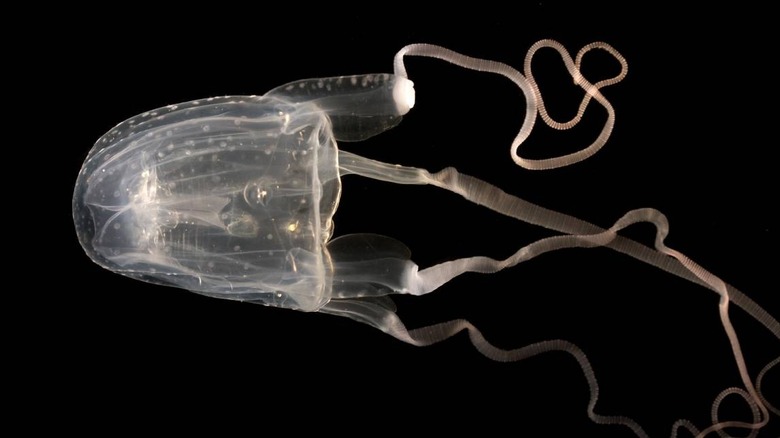

Of all the various types of box jellyfish, the Chironex fleckeri, also known as the "sea wasp," is the one you really don't want to run into. The sea wasp is pretty large, growing up to 10 inches wide; and, like other boxes or Cubozoans, can be distinguished by its cuboid bell-shaped head. The sea wasp has a cluster of long tentacles extending from each corner of its bell that can grow up to 10 feet long.

Being able to identify those features won't always do you much good while you're in the water. The sea wasp is transparent, making it all but invisible to swimmers, and can deliver enough venom in each sting to kill an adult. In Australia, it has accounted for 63 recorded human deaths in the past 80 years (per Scuba).

Its sting is described as feeling like "being whipped by hot wires" and can cause paralysis of the lungs or cardiac arrest within minutes. Survivors suffer pain for many weeks after their encounter. To make matters worse, the sea wasp likes to hunt during the day in shallow waters, which presents a considerable danger to unsuspecting holidaymakers enjoying the beach on the Australian coast and across the Indo-Pacific.

Chiropsalmus quadrigatus

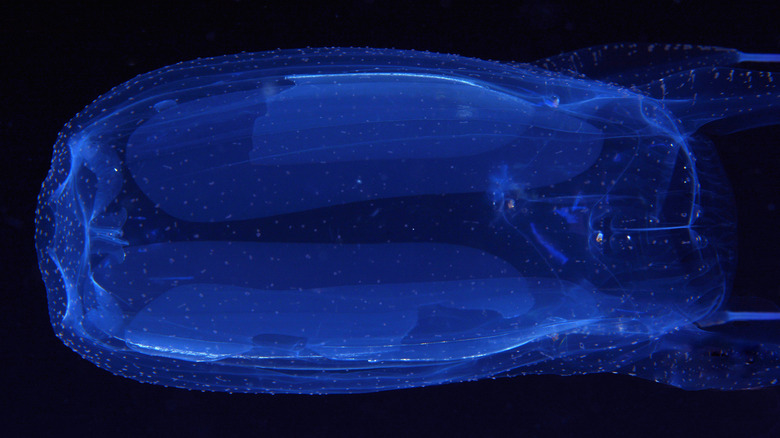

The Chiropsalmus quadrigatus is smaller than the sea wasp, growing to less than 4 inches wide, but it still packs a huge punch with a venom 700 times more powerful than the more well-known Portuguese man-of-war. They can be distinguished from their bigger cousins by four hand-like appendages at each corner of their bell head, each of which contains a cluster of long ribbon-like tentacles that are great for snaring its food as they jet about the ocean at speeds up to 5 mph. That's pretty fast considering the average human swimming speed is only 2 mph!

Like most box jellyfish, a sting from the Chiropsalmus quadrigatus can cause a range of horrible symptoms including cardiac arrest, respiratory failure, muscular cramps, delirium, convulsions, and even death — once its venom enters the bloodstream, it can paralyze the heart within 30 seconds. The agony caused by its venom has been described as "the most excruciating in the world" (Animal Diversity World).

Known as the more easily pronounceable "habu" in Japan, this box jelly frequents the waters of the Indo-Pacific region and the western Atlantic Ocean. The Japanese prefecture of Okinawa has encountered a surge in this kind of jellyfish infestation in recent years, with over 40% of incidents involving stings or bites by sea animals in 2022 attributed to the habu, according to the Okinawa Prefecture Department of Public Health and Medical Care.

Irukandji

Named after an indigenous Australian tribe, the Irukandji are the smallest known jellyfish in the world, growing up to an inch long with tentacles up to a meter in length. What they lack in size they make up for with their potential threat to humans; not only are they small enough to slip through holes in jellyfish nets, but they are also able to fire venomous stings from their tentacles and bell-shaped head. The Irukandji are even harder to spot in the water than other transparent jellyfish due to their tiny size; and, in Australia, they are responsible for between 50-100 stings requiring medical attention each year (per Great Barrier Reef Australia).

If stung, the biggest concern is that the victim will suffer from Irukandji syndrome. Symptoms can take up to 45 minutes to kick in before wracking the sufferer with severe pain, burning sensations, nausea and vomiting, cramps, and cardiac arrest, in some cases resulting in fatalities. Another curious side-effect is described as a "feeling of impending doom" which, according to Australian biologist Lisa Gerswhin, has provoked victims to beg for death, convinced they're already a goner (via Scuba).

They were originally native to Australia, particularly in the tropical climes of the North Coast, but have since expanded their range to Japan, Thailand, Florida, and even as far as the chilly waters of the British Isles.

Morbakka fenneri

Another native of Australian waters is the Morbakka fenneri, a species of Irukandji jellyfish that is evocatively known as the "fire jelly" due to its painful sting. Preferring the warmer waters to the north and east of the continent, it is most commonly found off the coast of Queensland. That doesn't necessarily mean they are restricted to those waters; in 2018, one was found floating in the relatively shallow waters of Lake Macquarie to the north of Sydney.

The good news about these guys is that they are a little more visible than some of the others mentioned here, measuring around 4 inches long and 2 inches across, which makes them somewhat easier to spot and identify. The other positive is that they aren't as deadly; while the Morbakka fenneri can still deliver a nasty sting and can potentially trigger Irukandji syndrome, a close encounter with a fire jelly tends to be unpleasant but not life-threatening.

Despite generally being considered less dangerous than other types of box jellyfish and Irukandji, it is still worth giving the Morbakka fenneri a wide berth. In 2015, a six-year-old boy from Wellington Point almost died after he was stung while swimming and lost consciousness. Thankfully, onlookers were on hand to help treat the wound until paramedics arrived and the lad was saved.

Alatina alata

The Alatina alata is a type of box jellyfish that grows up to 6 inches across and 12 inches long and makes the waters of Hawaii and the Pacific Ocean its home. Also known as the "sea wasp" in certain areas, it is the only known species of box jelly to swarm to shallower waters during certain times in the moon cycle, heading towards shore in the darkness before moonrise for 8-10 days after the full moon. Its sting is comparatively mild but can still cause severe discomfort and should be monitored. Like many other types of box jellyfish, it still has the potential to trigger Irukandji syndrome.

Since jellyfish aren't always easy to spot when you're in the water, one of the best ways to avoid stings is prevention. Swimmers should pay attention to warnings and wear a wetsuit to protect their skin. While walking on the shore, wearing water shoes is a good way to avoid accidental stings from treading on a beached jellyfish.

Fans of "Friends" all know the oft-quoted myth that urinating on a jellyfish sting will help. In real life, you're better off treating the affected area with vinegar or acetic acid and removing any visible tentacles before rinsing with clean hot water. If you suspect that you've been stung by one of the deadlier varieties, call emergency services (per Scientific American). Don't let this list put you off enjoying the sea, however; the chances of suffering a sting are still very slim, Dr. Lisa-Ann Gershwin told Great Barrier Reef Australia.